redacted from the fall 2016 Research Magazine

Its history stretches back 1,400 years. A landscape forming the traditional border between Christianity and Islam.

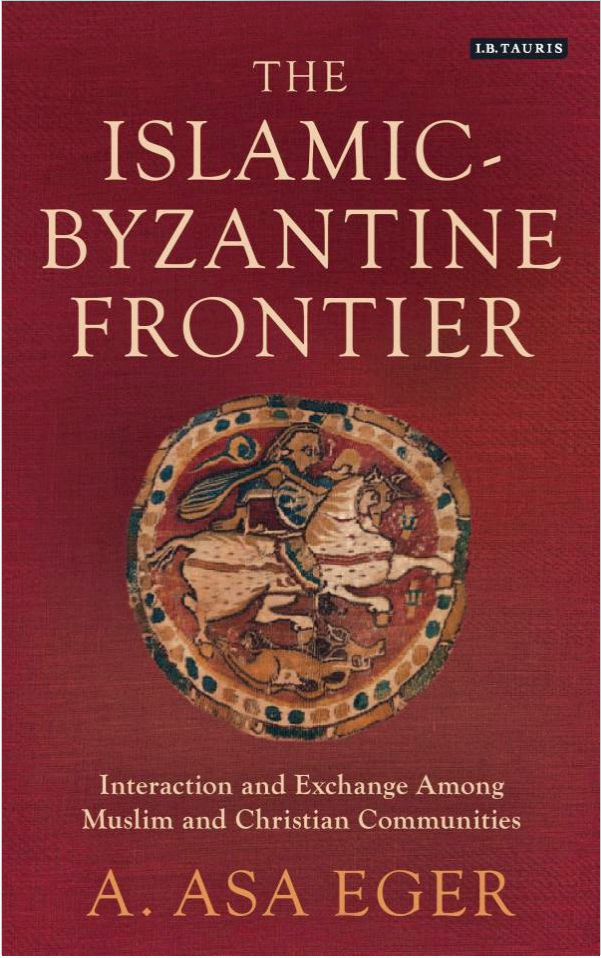

Dr. Asa Eger, professor of history, has explored the region — located generally along the border between today’s Turkey and Syria — with archaeological surveys and excavations. And now he has written the book “The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange between Christian and Muslim Communities.”

It’s an environmental and archaeological study of the longtime borderland from the 7th century C.E. onward.

The border has been traditionally viewed as the site of a clash of civilizations — where the Islamic and Byzantine empires continually fought, Eger explains. As far back as the Middle Ages, writers have depicted it as a bare, war-torn wilderness lined with fortresses.

![Image from an illuminated manuscript, the Madrid Skylitzes, showing Greek fire in use [Source: wikipedia.org]](https://research.uncg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Greekfire-madridskylitzes1-1.jpg)

Both sides conducted annual raids against one another for several centuries. The warring, framed as jihad on the Islamic side, was usually about resources — water usage, grazing rights, even access to timber and mines, Eger says. Islamic summer raids were also timed to correspond to the local nomads’ desire to find forage for their livestock.

“They’d trade and raid,” Eger says. Merchants moved between both empires freely. Commerce between Byzantine and Islamic lands flourished, while raids kept nomads preoccupied; both strengthened the status of those in power.

Eger’s work won the 2015 G. Ernest Wright Book Award from the American School of Oriental Research.

Eger’s work won the 2015 G. Ernest Wright Book Award from the American School of Oriental Research.

Eger notes that, in the past, the award has leaned toward Biblical sites and books. Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Classical strata at digs have traditionally gotten more attention than Islamic layers. But interests are changing.

“I was wonderfully surprised they gave the prize to Islamic research.”

Learn more at https://his.uncg.edu

redacted from “An ancient borderland” by Mike Harris, which originally appeared in the fall 2016 Research Magazine