Adapted from the spring 2017 UNCG Research Magazine

This is an intervention.

“A patient walks into their primary care physician’s office and fills out a short questionnaire about their alcohol use,” describes Jeremy Bray, professor and head of the Department of Economics. “Let’s say the patient has four or five drinks a week. The physician will say, ‘You’re doing a great job. Keep up the good work.’”

If the patient’s drinking habits are just outside the recommended range, but not so much as to cause alarm, the doctor offers advice on cutting back. “And if the answers seem to suggest the patient might have a disorder, the physician would encourage them to see a substance abuse professional who can help with an assessment and formal treatment,” Dr. Bray says.

“We tend to think about alcohol use as ‘yes, you are an alcoholic, or no, you’re not an alcoholic,’” he adds. “But it’s a continuum with different kinds of problems. For example, low levels above guidelines can disrupt sleep patterns and cause gastrointestinal issues. From a public health standpoint, we really want to address those things.”

This intervention, known as SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment), reduces alcohol consumption by an average of about two to five drinks a week. Studies have shown that excessive alcohol use is connected to a variety of social costs, like crime, traffic accidents, and extra healthcare visits, so it seems reasonable to suggest the intervention should be implemented across the board.

The thing is, Bray says, “there are a lot of recommended screening programs for physicians — mental health, substance abuse, hypertension, exercise, smoking,” just to name a few. “If physicians did every single recommended screening for their patients, it would take up more than their entire day. Physicians want to know which ones are the highest value.”

That’s where economists enter the picture. “Given that we are going to make an investment, we ask which one has the best bang for our buck,” Bray explains. Whether he’s reviewing programs or taxes meant to reduce alcohol use, Bray considers the benefits and the drawbacks. Only from examining every angle can he evaluate a policy’s true cost — and know when it’s worth it.

Investment versus impact

The majority of Bray’s research delves into alcohol prevention programs, but he looks beyond drinking outcomes to find ripple effects. “The theory behind these programs is that they will get people to change their drinking habits,” he says. “And if they do, we want to know if society will benefit. For example, if we increase the tax on alcohol, will there be an impact on things like wages and education?”

The majority of Bray’s research delves into alcohol prevention programs, but he looks beyond drinking outcomes to find ripple effects. “The theory behind these programs is that they will get people to change their drinking habits,” he says. “And if they do, we want to know if society will benefit. For example, if we increase the tax on alcohol, will there be an impact on things like wages and education?”

To determine a program’s value, Bray often chooses between two evaluation methods — a cost-benefit analysis and a cost-effectiveness analysis.

With a cost-benefit approach, or return on investment, economists look at the total amount spent and ask if the investor is saving money. An employer, for example, may invest in a workplace wellness program and want to know if the program is actually making employees more productive. “With this analysis, we are asking whether the employer is saving money,” Bray says.

On the other hand, a cost-effectiveness analysis doesn’t just look at cost savings, Bray explains. “It doesn’t only ask the question, ‘are we saving money?’” Imagine a hospital’s response when a patient comes in with a broken leg. “The hospital is going to treat it,” he says. “It’s not a question of whether it’s going to cost money. The question is, how do we treat it in a way that has the greatest effect for the least amount of money.”

According to Bray, with most programs, a greater effect follows a greater investment. “What you want to know is, is that extra effect worth the extra money. In other words, given that we will spend something, what’s our best value?”

Since the late ’80s, results from economists’ analyses on substance abuse programs have contributed to the debate on whether treating substance abuse is worthwhile. For a long time, it was treated as a weakness, not a disease, says Bray. “Certainly, now most physicians agree with the disease paradigm. Alcoholism may start with behavior choices, but substance abuse eventually alters brain functioning and brain physiology. It becomes a neurological disorder that needs to be treated.” But the rest of society doesn’t necessarily see it that way.

Returning to the broken leg analogy, Bray says substance and alcohol abuse have a barrier to overcome that other diseases don’t. “If you ask whether a treatment can save money, that implies the only reason to treat it is to save money. We don’t ask whether repairing a broken leg will save money. We just repair the broken leg.” People have more questions when it comes to substance abuse treatment.

Evaluating programs like SBIRT, which have a broad impact on society, can’t happen in a vacuum. Bray’s colleagues include experts in behavioral therapy, such as clinical psychologists and addiction therapists.

“I’ve led a lot of these evaluations, most with multi-disciplinary teams,” Bray says. Before joining UNCG, he served nine years as program director for the national cross-site evaluation of SBIRT programs funded by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Bray’s work supported the adoption of SBIRT reimbursement codes in Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance plans. Now, under the Affordable Care Act, screenings and brief interventions are a required preventative service—covered without insurance or copay. “My research has also influenced state and federal legislatures’ decisions on whether to move forward with SBIRT grants,” Bray says.

Ripple effects

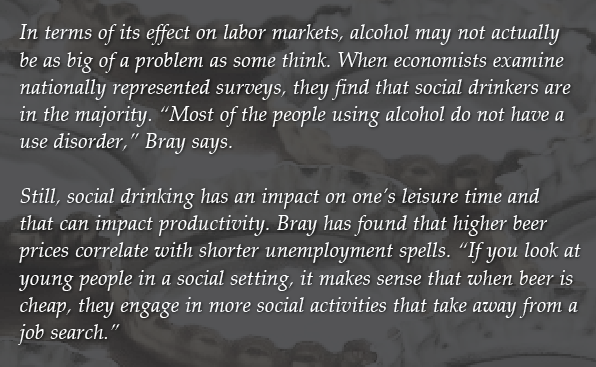

In addition to programs like SBIRT, Bray examines pricing and taxes — two areas of focus for policymakers hoping higher price tags will discourage alcohol abuse.

As an example, he points to the cigarette tax, which effectively caused smokers to curb their habit. At first glance, cigarettes and alcohol have a lot in common. Both can be detrimental to one’s own health and can cause negative ripple effects in society.

But unlike cigarette usage, which is discouraged at any level, economists don’t want to disincentivize a moderate drinker who causes no public harm. “If you have someone who is drinking one glass a night, it isn’t causing societal problems like someone who drinks eight to nine beers on a Friday night before driving home,” Bray says.

Economists help policymakers determine how they can implement policies that target the dangerous behaviors rather than impacting all drinkers, across the board. In European countries, Australia, and New Zealand, governments have implemented “minimum unit pricing,” a price floor rather than a tax, where drinks are priced according to how strong the unit of alcohol is.

With this type of pricing, a pint of an imperial stout with a higher alcohol count may count as 2.5 units as opposed to a pint of Guinness that counts as 1.5 units of alcohol. This type of policy can be effective because it targets the cheaper drinks that are more likely to be abused. “You don’t often see people drinking expensive microbrewed beers, or the high-end vodkas, with reckless abandon,” Bray says.

Bray’s particular interest lies not just in reducing consumption through taxes or price floors, but in pairing taxes with subsidies so that people change their consumption patterns. “If we borrow the cigarette model, you need to look at taxes and policies, and then you need to look at interventions that help people quit,” he explains.

When policymakers taxed cigarettes, they also provided coverage for smoking cessation therapies on insurance plans and nicotine replacement therapies. “People weren’t just forced to pay more money for cigarettes; they also received help,” he says. “Likewise, maybe we could increase taxes on beer sold in bars and use that money to subsidize treatments like SBIRT and alternate activities like local sporting leagues.”

Bray notes the user isn’t the only one impacted by taxes. He believes it’s important to consider the harm taxes cause by reducing profits of the alcohol industry. “If you look at Kentucky’s bourbon industry, that’s a core part of the state’s cultural heritage. We don’t want to tax those into non-existence.”

Bray’s research all leads to one definite conclusion: “The effects are more complicated than we might think,” he says. That’s why his work is so valuable to policymakers. “There are subtleties we need to understand. People make a whole suite of life decisions, and just because you change one of a multitude of decisions, it doesn’t mean you’ll get people on the right path.”

Learn more at http://bryan.uncg.edu/econ