redacted from the fall 2016 Research Magazine

“Three things are certain: death, taxes, and life-altering tests.”

They determine whether you get the job. Or pass the bar.

These tests will determine whether you advance to the next grade in school. Or whether you get into the university of your choice.

When you’re a 16-year-old set to take your SAT, you know what’s on the line. You’ve been receiving college brochures. Your school counselor tells you what you need to get into the top schools for your field. Your parents do too. A lot is riding on that score.

“The better the score, the better set you are for life,” says Professor Randall Penfield. “It’s a gatekeeper.”

Will it be fair? Will you be treated equally to the other students around you — or students around the country and the world? How can you tell it’s a level playing field?

Researchers are working to ensure the tests — and every item on them — are as fair as humanly possible, using sophisticated statistical methodologies. Penfield, an innovator in the field, is dedicated to the cause.

“I’m a little bit of an inventor,” he says. “I invent better methods — and using these methods leads to increased fairness.”

Measuring what you want to measure

Though he now serves as dean of the School of Education, Penfield joined UNCG to lead its Department of Educational Research Methodology, one of the largest in the nation.

Though he now serves as dean of the School of Education, Penfield joined UNCG to lead its Department of Educational Research Methodology, one of the largest in the nation.

A major focus of the department is an area called psychometrics, which deals with how to create tests of people’s knowledge and how to evaluate the quality of scores generated by those tests. Essentially, practitioners test the tests.

Penfield has authored or co-authored more than 50 articles and book chapters on psychometrics. His most recent is a chapter in the book “Fairness in Educational Assessment and Measurement,” published by Taylor & Francis. The chapter is “Fairness in test scoring.”

The chapter is math intensive, but math is just a starting point. “I think the numbers give you the first glimpse of whether there may be a problem in an item, but they don’t tell you everything.”

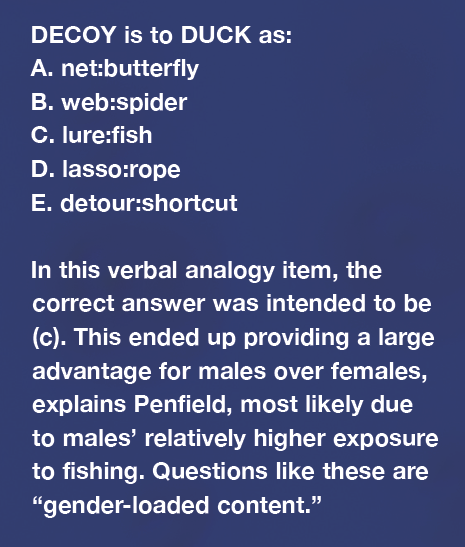

Statistical evaluation can reveal odd differences between groups for a test item. One state vs. another. One gender vs. another. One ethnicity vs. another.

The term is “differential item functioning” or “DIF.” It’s the extent to which a test item functions differently for different groups of test-takers.

It’s like a warning bell going off.

“The numbers may tell you there’s something funky going on—for whatever reason, it’s favoring one group over another. But you don’t know why exactly that is. The important step is to go back to the content to see why.”

You’re using high-level statistics—and more.

“It’s not as easy as looking at the numbers and away you go,” he concludes. “There’s an art to it as well.”

A social justice issue

How did Penfield come to be a leading researcher in this field?

“My dad is a statistician. My mom studied social justice. They were both professors.” He inherited both passions.

Penfield’s bachelor’s and master’s degrees were in psychology and physiological psychology, respectively. Then he discovered how he could make a huge impact, for good. He pursued psychometrics, with a doctorate in measurement and applied statistics.

“I do enjoy math, and I like to use data. But it allows me to get at these larger issues. Testing is an area that touches everyone—a key to some of our greatest points of access in our community.”

A lot of people in recent decades have been working to make tests more just.

“The assessment field has come a tremendously long way in improving the fairness of assessments. A lot of technology has been invented, a lot of math used, and lot of procedures created to get tests to measure what we want them to measure,” Penfield explains.

“Are you ever going to get to a place where a test is going to be completely fair across all individuals? That day is probably never going to come.”

But we can try to be as fair as possible, he explains. And then there’s another way to make testing more fair: Let’s offer tests in ways that will lead to fruitful results, he says.

“Let’s not use testing assessments to make decisions that will negatively affect people’s lives. Let’s use tests to help us inform better instruction, to help differentiate instruction as needed, to help show when a student needs a little extra attention in a particular area.”

Don’t use tests to bar the door. Use them to help students open doors to a better future.

The use of tests is oftentimes tied to policy, he says. That’s where tests are sometimes used in ways that don’t suit the greater good of the students. That’s where you have to be careful: How are these scores ultimately going to be used?

This is a multifaceted issue, one he has wrestled with since grad school. “How do we make things fair?”

The future of standardized testing

“The testing industry is a multibillion-dollar industry,” Penfield explains. Every testing company works to ensure each test item is accurate and provides the intended results.

“A lot goes into making sure results make sense.”

What sets Penfield’s work apart is his decade-long focus on performance assessment.

Multiple choice questions are common in standardized tests, he notes. But that’s shifting.

“Multiple choice has limitations. You can only go so far in digging out deeper levels of cognition and understanding.”

Until recently, most of the algorithms for determining bias had been for multiple choice tests. But his research looks to the next era.

“The future of testing is ‘performance assessment.’”

This could be, for example, a standardized test essay question that is scored across a range of categories. Or it could be a complex math problem, with various factors or steps receiving a score.

The answers are not true/false or wrong/right. Instead, the test-taker goes through a process, and they may get some credit for how well they perform in each step of the process.

“I am creating methods in detecting bias within those items.”

He is a research leader in this realm — developing algorithms and methods to determine bias within items in performance-based assessments.

An important consideration in performance-based assessments is who’s doing the grading.

“With performance-based assessments, humans are not always reliable. There are an infinite number of factors. Different graders may give different scores to the same writing sample.”

“Computers are perfectly reliable. They will always give you the same score.”

So computers seem to be where we’re headed, from fill in the blank to short answers to essays. But just like there’s unease with driverless cars—and 100 years ago there was unease with elevators not operated by humans, Penfield adds—there are lingering fears in our society with computers grading essays and similar tasks.

Computer grading is the future, like it or not, he says. Artificial intelligence is here, and it’s cost-efficient. “More and more, computers will score these assessments because humans are much more expensive.”

But while computers are reliable in that they will give you the same score every time, their findings are only as valid as the thinking behind the programs they run.

“With computer scoring of performance-based assessments on the horizon,” says Penfield, “the issue of fairness becomes more important than ever. We have to ensure that the algorithms used to conduct the scoring are functioning in a way that does not introduce unintended biases in the scores. This will take ongoing research.”

He is confident that researchers and those creating tests are up to the task.

“So much effort is going into ensuring the test is as fair as it can possibly be.”