redacted from the fall 2016 Research Magazine

When Donna Tuttle experienced the telltale signs of a heart attack — shortness of breath, tightening in her chest, extreme fatigue — she chewed two baby aspirins and took a nap. As a 48-year-old mother of four who had always prioritized exercise and nutrition, Tuttle never guessed heart disease. “I don’t smoke, I see my doctor once a year, my parents are living and in great health,” she says.

Two days later, Tuttle and her husband went for a leisurely walk through their neighborhood. She could barely make it home. This time, Tuttle went to the ER, where a CT scan revealed that one of her left coronary arteries was 99 percent blocked. “Even the cardiologist was shocked,” she says. “He told me I was a ticking time bomb. If I hadn’t come in, this would have caused a massive heart attack or instant death.”

According to the CDC, about 12 percent of Americans are diagnosed with heart disease. Still, the condition results in nearly one in four American deaths. Like Tuttle, most don’t know they’re at risk until they experience a heart attack.

Prognosticating

![Dr. Joseph Starobin (left) and Dr. Jared Lancaster brainstorm at the Joint School for Nanoscience and Nanoengineering [Photo by Mike Dickens]](https://research.uncg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Joeseph_Jarrett_Sitting.jpg)

By analyzing a heart’s electrical activity — the information you get from an electrocardiogram (ECG) — and looking specifically at how long it takes for the heart to contract and then recover from contracting, Starobin’s algorithm can pinpoint a person’s “optimum heart stability.” As long as their heart is performing in that range, they’re not at risk for heart disease.

“It is possible that many people could avoid heart disease entirely if they could recognize the warning signs,” says Starobin. Now, he and his research team are working to develop a wearable crystal ball, one that predicts heart disease long before a heart attack.

Picture any one of the many bracelet-type activity trackers currently on the market that provide personal stats ranging from daily steps to nightly sleep quality, says Dr. Jarrett Lancaster, a postdoctoral researcher in Starobin’s lab.

Now imagine if this tracker could know your optimum heart stability — when your heart is performing at its best — and could indicate when you should change your behavior to keep your heart healthy.

“Devices on the market can already show your heart rate,” Lancaster explains. “But alone, your heart rate doesn’t tell you when you’ve reached thresholds that would indicate you’re at risk for heart disease.”

Let’s say your optimum heart stability is 100 percent, he continues. “Most healthy people going about their business are anywhere from 85 to 100 percent.” But when an individual’s heart stability drops down to 70 percent, they have no way of knowing it.

“There aren’t any apparent physiological changes, but that is really the critical time where you could make changes in your fitness, nutrition, or stress to bounce back to the healthy zone,” he says.

To Market, To Market

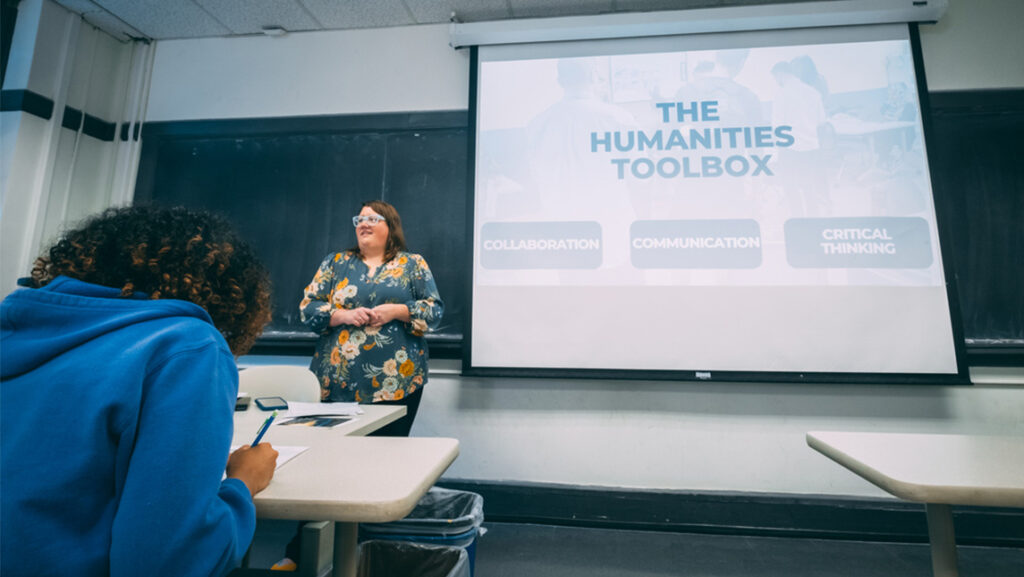

It took years for Starobin to develop a groundbreaking algorithm with the potential to save lives. But connecting with a company that shares a scientist’s vision — and knows how to bring new technologies to market — takes more than time. In the case of Starobin and Lancaster, the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps program provided that bridge between idea and product.

“I-Corps is designed to get researchers out of the lab and into the market,” says UNCG Office of Innovation Commercialization director Staton Noel. “The focus is on customer discovery.”

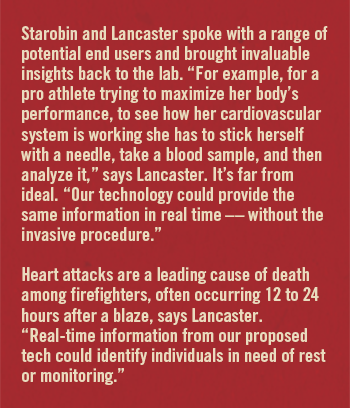

As their I-Corps mentor, Noel helped schedule interviews between Starobin’s team and more than 100 customers and businesses in seven weeks. “They started by talking to customers who use things like Fitbits to monitor their health,” he says. “Then they moved on to talking to the providers of that technology. Every week, they increased their understanding of how their technology could be used in the real world.” They identified their customer base: medical professionals concerned about heart disease prevention, the fitness community, and people in high-risk professions, like firefighters.

Starobin and Lancaster then discovered partners willing to work toward the same objective. They connected with Monebo, a software company whose technology can intercept the heart’s raw electronic signal and turn it into a clean, readable format. “Picking up a heart’s signal is like listening to a radio station full of static,” Lancaster says. “Monebo helps you tune in to the right station.”

Starobin and Lancaster then discovered partners willing to work toward the same objective. They connected with Monebo, a software company whose technology can intercept the heart’s raw electronic signal and turn it into a clean, readable format. “Picking up a heart’s signal is like listening to a radio station full of static,” Lancaster says. “Monebo helps you tune in to the right station.”

They also partnered with Rhythm Diagnostic Systems, a company with the potential to take Monebo’s data, run it through Starobin and Lancaster’s algorithm, and display it on the wearable device.

For Tuttle, this technology can’t come fast enough. “Since I can’t see how my heart is performing, I live with this nagging doubt. Every time the doctor checks my cholesterol and weight and BMI, and my numbers come down, that’s huge for me,” she says. “Any tool I have to give me an indication of how things are going is helpful.”

With his new partners, Starobin believes his dreams for the algorithm will become a reality. “I’ve worked years to develop this algorithm. But before, there was no way to marry all this knowledge with any particular device. Now, it’s all possible.”

Learn more at https://innovate.uncg.edu & http://jsnn.ncat.uncg.edu