In the summer of 2023, a group of eight UNCG students embarked on a journey to a Middle Eastern excavation site, led by Dr. Asa Eger.

Caesarea Maritima, a Mediterranean port city, was the capital of the Roman and the Byzantine provinces of Judaea, Syria Palaestina, and Palaestina Prima. Now, it is part of the Caesarea National Park in Israel.

The area is a busy excavation site as well as a tourist attraction. It was an excellent destination for students to gain experience excavating material culture artifacts for research studies while also interacting with a host of cultures.

Work continued even after students returned to North Carolina. Over a year later, students in Dr. Charles Egeland‘s lab continue to conduct research with animal bone samples uncovered during the expedition.

Can You Dig It?

As plans were coming together for the trip to Caesarea, then-first-year Sebastian Astorga, a history major, was taking his very first history course at UNCG – Islamic Civilization with Eger, a professor in the department. “I have always been interested in the history of the Middle East,” Astorga says. “It’s the birthplace of civilization.”

Eger noticed his interest and shared an opportunity for Astorga to participate in a UNCG Undergraduate Research and Creativity Award (URCA)-funded project he was working on with then-senior Samuel Feinstein.

In preparation for the trip to Caesarea, they had researched artifacts previously recovered at the site and noticed that many materials were uncovered from houses inhabited by Muslim Bosnian refugees – and their descendants – who had lived in a village that existed there from roughly 1880 until 1948. These Bosnian items had been set aside as archeologists dug deeper for Islamic or Crusader artifacts from older civilizations, but Eger took a different perspective.

“We could have gone under the Bosnian belongings in search of Roman artifacts like all the other teams,” Eger says, but instead of casting this later era of history aside, the team intentionally chose the site of a Bosnian village house for their study.

“Samuel was taking the oral history side of the project, and they needed someone to handle the material culture and archeology side,” says Astorga. “This was a very cool opportunity to go to an ancient excavation site and see something relatively new from history.”

Unearthing Connections

While on the trip, the students got hands-on experience as they carefully extracted and cleaned materials from the dig, sorted and labeled findings, and recorded oral histories from people with connections to the houses.

Feinstein’s oral history research explored how the Bosnian refugees and their descendants had lived. A connection with a family friend of Bosnian heritage helped him find several interviewees in the area with links to the old village.

“We had this procedure we followed when we reached out to interview descendants,” Eger says. “We’d pick them up and take them to the park, show them the remains of the house we were excavating and what we had found, and then we’d record their oral history.”

One of their interviewees was a man whose grandparents had lived in the village. “He told us how he brings his kids here all the time, but there’s nothing to show them. It was powerful for him to see what we were uncovering. In turn, he was able to share memories about the house and activities that happened there. It was amazing for us to get that information.”

“At the end of our excavations, I met with the park director and showed him everything we had uncovered from the Bosnian house,” Eger says. “I explained that what we’d really like is for the park to conserve it and post a physical marker to memorialize the existence of the village, so tourists can learn more about this part of Caesarea Maritima’s history. He was very interested.”

After returning to UNCG, museum studies master’s student Deborah Aronin and history doctoral student Jeanna DeVita Strickland continued to work on ways to preserve the Bosnian village in collaboration with the nearby Sdot Yam kibbutz, which was established in 1930. The result: a virtual exhibit, in its early stages of development still, that combines archival materials and interviews to tell the story of the early years of coexistence and cooperation between the kibbutz and the Bosnian village.

Digging Up Multidisciplinary Research

While Astorga and Feinstein were unearthing the story of a Bosnian settlement, anthropology professor Egeland and his class were exploring the diet of 12th-century Muslims in the area.

“People are interested in other people. You want to know about their daily lives. Archaeologists can’t interview people, so we have to look at the remains that they leave behind to get the answers,” says Egeland, who directs UNCG’s Archeology Program.

With URCA funding, then-third-year anthropology major Matt Henderson collaborated with Egeland to create a protocol for uncovering bones that potentially represented ancient meals, as well as cleaning and categorizing them. At the site, he taught fellow student researchers basic identification methods.

“Humans have a rich cultural connection to the things that they eat,” Egeland explains. “Looking at the animal bones not only gives you a kind of menu of what’s being consumed by these communities, but you can also talk about why they’re making those decisions.” During the dig, the researchers found a lot of cattle remains, some pigs, and a handful of horse remains.

Back at UNCG, Henderson and other undergraduate students in Egeland’s zooarchaeology course analyzed the bone samples, with Henderson presenting his results at the UNCG Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo. Volunteers continue to explore the Caesarea bones under the direction of research assistants, including anthropology alumni Hunter Shields and Maegan Ferguson.

Raising History

Uncovering forgotten histories made for an impactful research project for the UNCG students and faculty members involved in the 2023 dig.

For example, though the Bosnian families he studied were across the globe and from another time, Astorga uncovered similarities between his own life and that of the family he was studying.

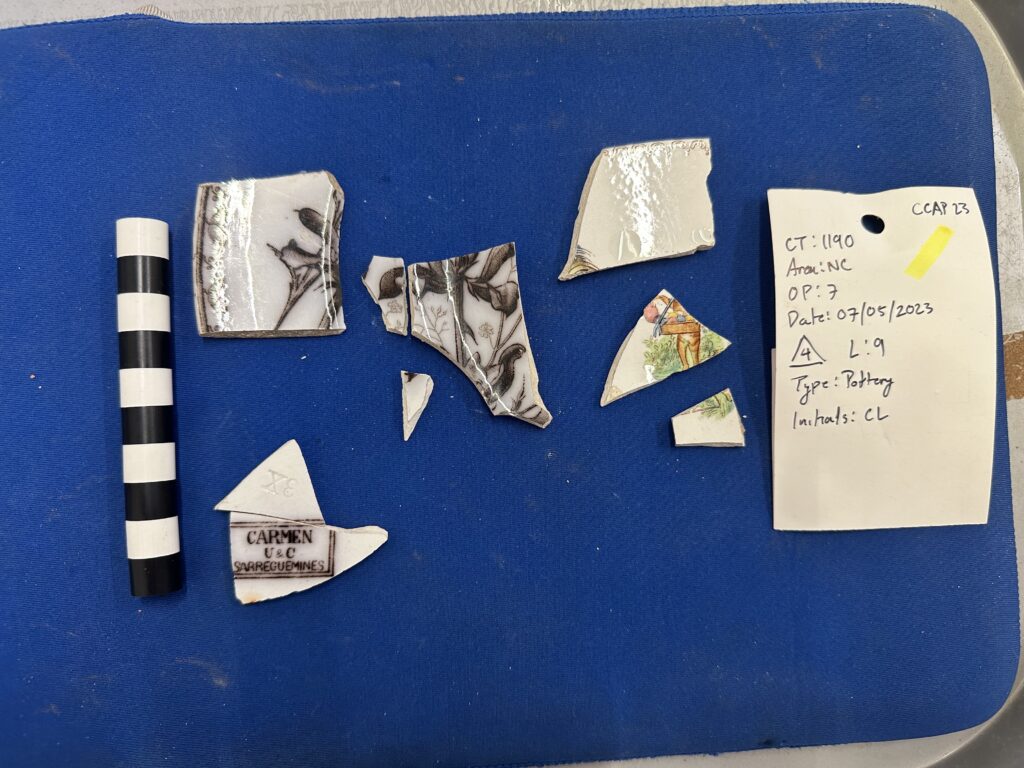

“When we were excavating, we found plates with a little symbol on them. One of them had a bunny, and it reminded me of plates that my mom uses at Easter,” he says. Astorga’s mother, the owner of an antique store in Chapel Hill, helped the researchers identify the relic as a hand-painted Easter bunny and part of a porcelain tea set from Europe, possibly intended for children.

“I felt a personal connection to the research I was doing and what I was contributing,” he says.

Story by Becky Deakins and Nikkola Brown

Photos courtesy of Dr. Asa Eger and Sean Norona