Article by Ananya Huria and Sangeetha Shivaji

Human leishmaniasis is one of the most common vector-borne diseases in the world, ranking alongside illnesses such as malaria and dengue fever. Caused by Leishmania protozoa and transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies, the various forms of leishmaniasis are typically found in arid, semi-arid, and tropical regions.

Approximately 350 million people worldwide are at risk for leishmaniasis. Most live in the poorest regions of the world, and, as a result, leishmaniasis is a neglected disease. Occurrences are under-reported, research is under-funded, and health care is inadequate. Leishmaniasis is also a major cause of infectious disease incidence among military personnel deployed in endemic areas and among tourists and aid-workers.

Female sand flies require blood for egg development.An estimated 1 to 1.5 million cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis, characterized by ulcerating skin lesions, occur annually. The world also sees about 500,000 yearly cases of the deadly visceral leishmaniasis, which attacks vital organs. While treatments for leishmaniasis are available, cost, access, and side effects limit their effectiveness. With no vaccine to protect against Leishmania protozoa, the most effective way to combat the disease is to reduce exposure to sand fly bites.

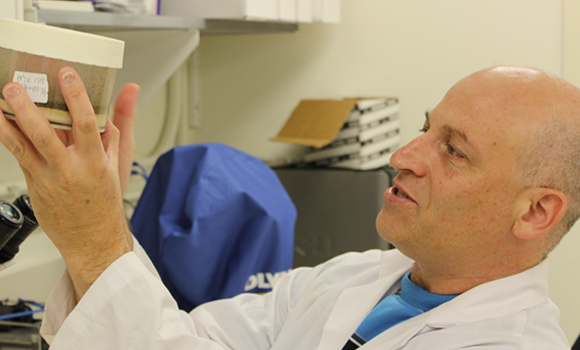

UNCG’s Dr. Gideon Wasserberg studies the behavior of Phlebotomus papatasi, the sand fly that transmits old-world cutaneous leishmaniasis. The assistant professor of biology is seeking an effective yet environmentally-friendly way to prevent the disease. His plan? To develop a lure that will attract and kill egg-bearing sand flies searching for suitable breeding sites.

A $300,000 multidisciplinary research grant from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center supports Wasserberg’s collaborative work on this project with North Carolina State University entomologists Coby Schal, Loganathan Ponnusamy, and Charles Apperson.

Female sand flies, who require blood for egg development, pick up Leishmania protozoa by feeding on the blood of infected animals. (Subsequent bites can spread the disease to humans.) In their natural environments, Ph. papatasi sand flies mainly use rodents as their source for blood meals, shelter, and even breeding sites. The flies lay their eggs in clusters of decomposing organic matter in rodent burrows. Wasserberg hypothesizes that the decomposing matter in these burrows produces chemical cues that attract egg-bearing sand flies. The cues, which come from bacteria in the decomposing matter, indicate suitable sites for egg laying. If elucidated, these cues could also be perfect lures for sand fly traps.

Bahjat Fadi Marayati is a graduate student in the Wasserberg lab. Wasserberg is originally from Israel, and Marayati is from Syria. Both countries’ populations are at risk for Leishmaniasis infections.Wasserberg and his colleagues are employing a four-step strategy to find the ideal chemical blend to use as a lure. First, Dr. Wasserberg will use behavioral bioassays to screen different materials to determine which ones are most attractive to egg-laying females. Then, Drs. Ponnusamy and Apperson will use molecular and selective culturing methods to determine which members of the bacterial community contribute most to the attractiveness of these materials. Next, Dr. Schal will use gas-chromatography coupled to electro-antennographic detection analysis to identify odorants arising from the those particular materials and bacteria. Finally, using behavioral bioassays once more, Dr. Wasserberg’s lab wil confirm whether the identified odorants are attractive individually or in blends and optimize the most attractive blend.

If Dr. Wasserberg and his colleagues are successful, the resulting attract-and-kill commercial sand fly traps will help control Ph. papatasi sand fly populations, thereby reducing Cutaneous Leishmaniasis burden in endemic regions. Researchers could then apply Wasserberg’s approach to other sand fly species in other Leishmaniasis-endemic regions of the world, contributing to the worldwide prevention of this devastating disease.

Dr. Wasserberg wants to contribute toward North Carolina’s economic development by collaborating with local companies to produce his lures and traps. He also hopes his work will promote the health of American soldiers deployed in Leishmaniasis-endemic regions.

The North Carolina Biotechnology Center’s multidisciplinary research grant is designed to foster interdisciplinary collaborations on complex problems that require more than one area of expertise to solve. Winning projects involve North Carolina researchers from three distinct disciplines working together for advancement of the state-of-the-art in biotechnology and cultivate early stage collaborations on new ideas.

Photography by Ananya Huria

Article author Ananya Huria is a Media and Communication Intern with the UNCG Office of Research and Economic Development, where she helps promote UNCG research stories and impact to campus and external audiences. Ananya is a senior at UNCG, studying international business and entrepreneurship. Her background in PR and Marketing lead her to her current position.

Article author Ananya Huria is a Media and Communication Intern with the UNCG Office of Research and Economic Development, where she helps promote UNCG research stories and impact to campus and external audiences. Ananya is a senior at UNCG, studying international business and entrepreneurship. Her background in PR and Marketing lead her to her current position.